The date is June 14, 1962, in Boston, Massachusetts. Ana Slesers is getting ready to meet her son for a memorial service in the evening when there’s a knock at the door. A man, claiming to be a maintenance man or perhaps a salesman meets her there, persuading his way into her home innocuously. He takes care of his business and is gone.

When Ana Slesers’s son came to pick her up, there was no answer at the door. In fact, the door was locked from the inside. He forced it open and found his mother on the ground, dead with the cord of her bathrobe wrapped around her neck and tied in a bow.

On June 28, Mary Mullen was found in her home having died of a heart attack as she was assaulted. Two days later, Nina Nichols was discovered with her stockings tied in a similar bow, on the same street as Mullen. On the same day, Helen Blake’s body was found as well.

The names continued for two years. On August 19, Ida Irga, August 21 Jane Sullivan. There is a break for a few months before Sophie Clark on December 5 and Patricia Bissette on December 31. Mary Brown on March 6, entering into 1963, and Beverly Samans was stabbed to death on May 6. Joann Graff on November 23, 1963, and finally Mary Sullivan on January 4, 1964.

There are few common threads that can be laced among the women. They ranged greatly in age, from 19 to 85. They didn’t share elements of their appearance. While all the murders were in Massachusetts, bodies were found in Boston, Lynn, Lawrence, Cambridge, and Salem. The women didn’t often share similarities, a practice that is not usually found in serial killers’s selection of victims. Police didn’t think of the murders as all being connected, but rather as individuals who suffered similar circumstances by coincidence. Specifics of the cases, such as the bows around their throat, were not released to the media or the public.

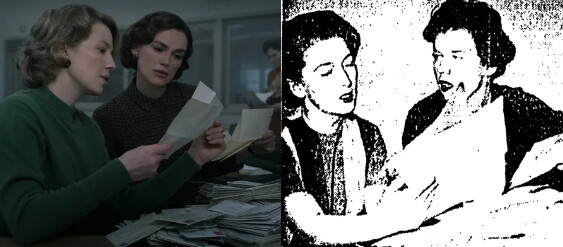

1963 was when the case truly gained traction. Reporters Loretta McLaughlin and Jean Cole of the Record Americanstarted publishing a series of articles about the murders. It was these accounts that first dubbed the killer as the Boston Strangler and the first time all of the murders were connected together. Working with members of the police force, McLaughlin began to publish the covert information, publicizing the odd connections between the cases. At her claims, police were forced to entertain the idea that it was actually the work of a serial killer and not copycat criminals or face the wrath of the public.

Boston and its surrounding areas were struck by a panic. Women were advised not to go out alone and if they lived alone they purchased deadbolts. Most of the people walking past on the street were armed with tear gas, pepper spray, or hatpins prepared to wield anything as a weapon. Some women simply sold their homes and moved.

All the while, McLaughlin and Cole were left dodging threatening calls and angry conversations with their editors. The police were unamused that so much information was given to the public without their approval and the Record America was under fire. But it did not stop them from writing their articles and promoting awareness of the case.

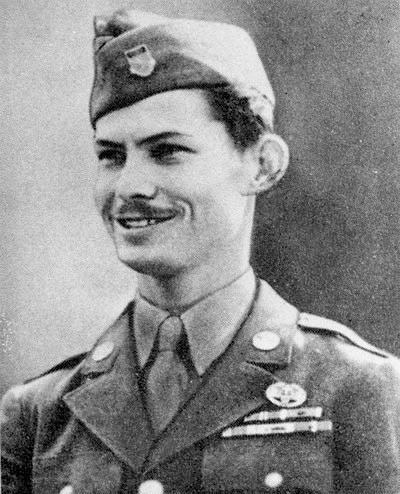

Albert DeSalvo was first arrested when he was 12 for battery and robbery. Then again three years later for stealing a car. When he was released he joined the army but was honorably discharged not long after. He re-enlisted but was discharged again.

In late 1964, DeSalvo was arrested for charges having nothing to do with the Boston slayings—rather, he was pinned as the “Green Man” who was accused of posing as a detective to infiltrate women’s homes and assaulting them. After a photo of him was released, many women came forward claiming to have experienced the same thing. The more claims, the more the police considered him to be the Boston Strangler.

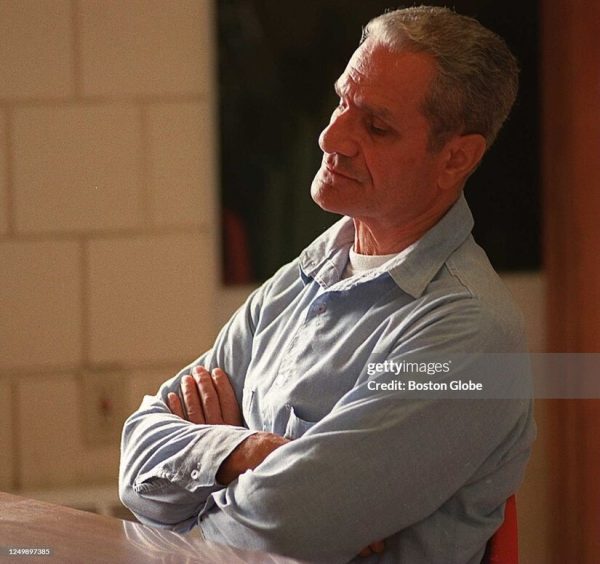

George Nassar was arrested around the same time as DeSalvo for the murder of Irvin Hilton, a gas station owner. He was placed under observation for schizophrenic tendencies. Previously, he had been imprisoned once before after shooting a shop owner during a robbery and stealing a car but had been released on parole just before the Boston Strangler murders began.

Nassar and DeSalvo met in prison. Supposedly, DeSalvo admitted to the string of murders to Nassar who immediately called his lawyer. Although DeSalvo didn’t have all the details correct and no physical evidence connected him the the crime scenes, he knew more than the general public could have known. Nassar’s lawyer decided to take DeSalvo’s case on and attempted to plead insanity.

DeSalvo was never formally charged as the Boston Strangler. But he was sentenced to life in prison on other related charges. As far as facts goes, no one knows who the murderer really was. DeSalvo’s DNA has since been found at Mary Sullivan’s crime scene, but none of the others. In February of 1967, he escaped the jail in an effort to protest the poor conditions at Bridgewater State Hospital. He and two other inmates were promptly caught and moved to a maximum-security prison. DeSalvo stayed there until his death in 1974 when he was stabbed to death in the infirmary for selling smuggled drugs at the incorrect price.

While DeSalvo is often regarded as being the Boston Strangler, there is still a lot of speculation surrounding it. Popular theory proposes it was Nassar who committed the murders, a secret mastermind, feeding all the information to DeSalvo and encouraging him to confess. Both had life sentences, neither had anything to lose, and a monetary award to gain for the admission of the Boston Strangler.

Whoever the killer (or speculated killers) may have been, it’s still important to recognize the thirteen innocent women who lost their lives to pointless violence. And even more so Loretta McLaughlin and Jean Cole, who risked their entire careers to make those women’s names and stories known.

For more on the Boston Strangler and the tribulations of McLaughlin and Cole, check out Boston Strangler on Hulu starring Kiera Knightley.