Celebrating Women’s History Month

March 25, 2022

Marsha P. Johnson

Marsha P. Johnson was a black, transgender activist who fought for LGBTQ+ rights and led the Stonewall Riots.

She was born on August 24th, 1945, in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Johnson was assigned male at birth, but she loved playing dress-up and putting on makeup as a child.

She felt comfortable in clothes that were made for women, but after a boy sexually assaulted her, she stopped wearing them until she graduated high school and moved to New York City. She only had $15 and a bag of clothes.

In New York City, she started using the name Marsha P. Johnson, the “P” standing for “Pay it no mind,” which was a motto of hers and an answer to people who asked about her gender.

Despite the word “transgender” not being popular when she was alive, Marsha was a part of the growing LGBTQ+ community that was constantly fighting for rights.

Marsha had trouble finding work, no one wanted to hire a black transgender woman. The fastest way for her to make money was through sex work. This was an extremely dangerous thing for her to do, she was constantly threatened and once even got shot.

Housing was not a constant in her life, Johnson often slept in movie theaters, hotels, or stayed with friends, Eventually, she found work waiting tables and as a drag queen.

Marsha made a lot of her own clothing, from fabric she found at thrift stores, and things she picked up on the street.

On June 28, 1969, the police raided a gay bar, Stonewall Inn. Marsha was nearby. The police arrested people for breaking homophobic laws, and the people fought back. No one knows for sure how the uprising started, but Marsha was at the front of it, as were many trans women. They didn’t have anything else to lose.

The Stonewall Riots lasted six days, but the impact was colossal. Soon, Marsha was going to rallies and sit-ins. Even still, however, the conversations were overwhelmingly about white gay men and lesbians, not black trans people like Marsha who were more likely to be homeless. The riots didn’t do much to help transgender people who needed it.

In 1970, Sylvia Rivera, a transgender Puerto Rican woman whom Marsha had befriended, came up with an idea. They were going to give young transpeople a home. This idea formed into the Street Transvestite Activist Revolutionaries, or STAR. They set up various housing complexes in an abandoned truck, but after they realized the truck hadn’t actually been abandoned, simply vacant, they knew they needed a better home for their transgender “kids.”

They rented a building with no running water and no electricity, as it was all they could pay for. They fixed it up and paid rent for eight months until they could no longer afford it.

STAR continued to be a voice for the transgender and gender non-conforming people in the area. The organizers of the gay pride parade tried to ban STAR from attending, and they showed up anyways to support their transgender peers.

Marsha soon became popular in Greenwich Village, where they began to call her “Saint Marsha.” She had a reputation for being generous, even when she didn’t have much herself. Marsha lived in constant danger, she was arrested over 100 times.

In 1990, Marsha P. Johnson contracted AIDS. She was very vocal about it, hoping that others with the disease wouldn’t have to live in shame and fear.

In 1992, Marsha died. Her body was found floating in the Hudson River on July 6. The police ruled her death a suicide, despite her close friends saying she was not suicidal. It is more likely Marsha was the victim of a hate crime. The LGBTQ+ community was enraged that there was no investigation into her death. At her funeral, hundreds of people showed up to honor Marsha.

The case was reopened in 2012 but is yet to be solved. In 2019, New York City announced that they would put up a statue of Marsha and Sylvia. In 2020, they named a waterfront park in Brooklyn after her. In August of 2021, activists unveiled their own statue of Marsha in Christopher Park while waiting for the city to build the one they promised.

Marsha P. Johnson has continued to inspire people of the LGBTQ+ community to fight for what they have been denied for centuries. Without her, America would be a much less accepting place for millions of people.

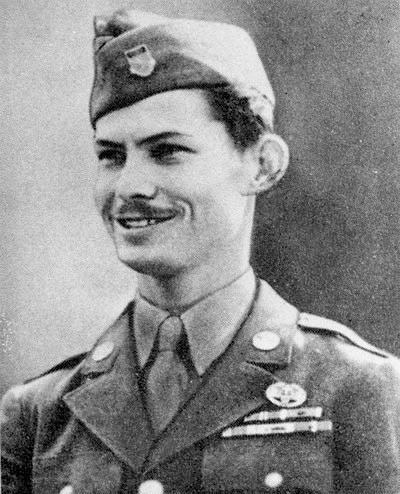

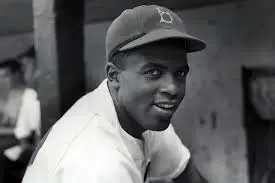

Jackie Mitchell

Jackie Mitchell was the second woman to sign a contract with a professional baseball team and is famous for striking out Babe Ruth.

Jackie, born Virne Beatrice Mitchell, was born and raised in Chattanooga, Tennessee. She learned to play baseball with her father in a park near their home. She also played with Dazzy Vance, a future Hall of Fame pitcher, who lived near her home.

Jackie played sports all year, not just in baseball season. She played basketball in the winter, and baseball in the warmer seasons. When the owner of the Chattanooga Lookouts, Joe Engel, offered to sign Jackie to the Lookouts, she was playing a basketball tournament in Dallas. But she ditched that for a chance to play professional baseball. She was 17 years old at the time. Jackie was the second woman to sign a contract to play professional baseball, coming after Lizzie Arlington who played for the Reading Coal Heavers of the Atlantic League.

The Yankees were set to play the Lookouts on their way home from Spring Training. This team’s most notable players were Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

The press was eager to get details of the game. While waiting for it, many newspapers wrote about Jackie, often saying sexist things instead of talking about her skills as an athlete. They talked about how pretty she was and one paper said she “ pulled out her mirror and powder puff, and dusted the shine off her nose.” Another commented on her lipstick.

When the game finally came, and it was time for Mitchell to pitch, the first two batters were Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

When Babe Ruth stepped up to the plate, he tipped his hat at Mitchell. She threw the ball and it missed the zone for a ball. But her next three pitches made history. Babe Ruth swung and missed the first two, and the third barely grazed the bat. But the umpire ruled it as a strike. The man threw his bat to the ground, but the facts were plain and simple. A 17-year-old girl had just struck out Babe Ruth.

Next was Lou Gehrig, who had three pitches thrown to him and he missed them all. The Yankees would win that game, but the headlines were all about how Jackie Mitchell had struck out two of the best players the Yankees had.

There were skeptics, however. Misogynists all wrote about how the two male players had played the game well, and heavily implied that the strike-outs were a publicity stunt. No one involved ever admitted to it being one.

Mitchell herself commented on the pitches in 1987, a solid 50 years after the fact. She said she struck them out fairly and that “better hitters than them couldn’t hit me. Why should they’ve been any different?”

Mitchell’s contract was ended soon after the game.

She signed on with the Hosue of David team, a religious group. Mitchell didn’t like how they didn’t take the game seriously, so she retired and moved back to Chattanooga at the age of 23. Mitchell died in Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia in 1987, survived by her nephew and cousins.

Mitchell’s story fits with many others, that when a woman comes into a male-dominated field and does better than the men, she may not end up winning.

Frances Perkins

Frances Perkins was the first woman to ever serve in a presidential cabinet.

She was born Fannie Coralie Perkins in Boston in 1880. Her parents were from Maine, but after the Civil War, they moved to Massachusetts.

The Perkins family was strictly conservative Republicans. Frances and her sister, Ethel, largely socialized with people from the nearby Plymouth Congregational Church. She’d only encountered poverty when she entered school. When she asked her father why some people were poor, she was met with the standard answers of the time that they were drunk and lazy. Then she was told that young girls shouldn’t be concerned with such things.

Frances graduated from Worcester’s Classical High School and went on to Mount Holyoke College, which was both founded by a woman and encouraged young women to get educated. Perkins majored in physics and minored in chemistry and biology.

Perkins graduated from Mount Holyoke in 1902. Her parents expected her to come home and get a job teaching, or in the church until a prospect for marriage appeared. But Frances wanted to be employed in social work. Eventually, this was unsuccessful, and she left Worcester to teach at an elite school for girls in Illinois.

In Chicago, Frances volunteered to help the poor and unemployed. She became further enraged with the hazardous world they constantly lived in, when much of the poverty was unnecessary in her mind.

In 1909, Frances studied sociology and economics at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. She earned her Master’s Degree at Columbia University.

In 1910, her goal of social work was accomplished. Frances became the Executive Secretary of the New York City Consumers League. She advocated for the need for sanitary regulations for bakeries, fire protection for factories, and legislation to prevent people from overworking themselves.

On March 25, 1911, there was a huge fire in a factory. Frances witnessed people, mostly women, jump onto the streets from eight stories up to avoid the flames, only to die from the fall. 146 people died that day in this fire. This fire was, to Perkins, “the day the New Deal was born.”

Frances was hired as the Committee on Safety’s executive secretary, at the suggestion of Theodore Roosevelt. One of the first actions of the Committee was to study and promote fire safety along with health threats to people working in factories. Perkins was an expert in this field and led legislators in inspections of factories and worksites. Seeing the terrible conditions she’d pointed out to them, laws were quickly put in place to prioritize the safety and health of the workers.

When Al Smith was elected as governor of New York, he appointed Perkins on the New York State Industrial Commission. She was the first woman to be appointed to an administrative position in New York.

New York’s next governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, appointed her as the state’s Industrial Commissioner, where she would manage the entire labor department.

At the beginning of the Great Depression in 1930, Perkins openly challenged the president, Herbert Hoover’s administration about the unemployment rate. Hoover was confident that the country was on an incline in employment rates, but Perkins knew otherwise and wanted the people to know.

The presidential election in 1932 was won by Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt asked Frances Perkins to serve in his cabinet as Secretary of Labor. She made a list of policies and priorities to pursue to help the public, like a 40-hour workweek, minimum wage, abolition of child labor, and more. She made it apparent that if Roosevelt wanted her, he needed to make these issues a priority. He agreed, and Perkins became the first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet.

One of the most influential things Frances accomplished was helping create the New Deal. The New Deal was a series of public work programs, financial reforms, and regulations to help the country recover from the Great Depression. It worked to help Perkins accomplish many of her original terms for being in Roosevelt’s cabinet.

By the end of Roosevelt’s presidency, Frances had accomplished every goal on her list except one: universal healthcare.

Under the next president, Harry S. Truman, Perkins was appointed to the United States Civil Service Commission. She held the job until 1953. Then she began teaching writing and public lectures at Cornell University until her death in May 1965. She died from a stroke at the age of 85 years old.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Sister Rosetta Tharpe was a black, queer Rock and Roll icon who influenced some of the best artists of the rock music movement.

Born Rosetta Nubin in Cotton Plant, Arkansas in 1915, both her parents were passionate about music. Her mother was a preacher at the local church, where they worshipped through musical expression.

Tharpe was described as a musical child prodigy, singing and playing guitar at four years old.

At six, Tharpe was a performer in a traveling evangelical troupe where she played with people like Duke Ellington.

She eventually settled in Chicago and married Thomas Thorpe at the age of 19. Their marriage didn’t last long, but she did take his last name and use a form of it as her stage name: Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

In 1938, Rosetta recorded her first pieces of music, the first time a gospel act would be recorded for Decca Records, the label that recorded with other popular artists. Tharpe wasn’t quite that popular yet, but she was rising. She came out with her first hit “Rock Me” at this time.

Tharpe performed both as a solo artist and with groups, many of which being all-white groups. Most people had never seen a black woman playing the electric guitar. But she captivated audiences nonetheless. Sister Rosetta Tharpe brought gospel music into popularity, and practically invented her own genre that combined jazz and blues with gospel music.

In 1944, Tharpe released “Strange Things Happening Every Day” which became the first gospel song to chart on Billboard’s Harlem Hit Parade, now called the R&B chart. This song is considered by some to be the first rock song.

One night in 1946, Tharpe saw Marie Knight and Mahalia Jackson in concert. She was in awe of Knight and sought her out to perform together. The two became creative partners and got into a romantic relationship.

Tharpe toured and made music in the 1950s and 1960s. She performed at an abandoned railroad station in 1964, a show that was broadcasted to all of England. But the sixties were when her popularity faded.

Compared to her white male counterparts, no one wanted to listen to Tharpe’s religious rock music. She was upstaged by artists who took for granted the movement she helped create.

Many artists like Elvis, Aretha Franklin, and Johnny Cash have credited Sister Rosetta Tharpe with inspiring their work.

Tharpe died in 1973 in Philadelphia surrounded by her mother and Marie Knight.

She was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2018, 45 years after her death. She is now considered a creator of the rock and roll movement.

Although she is often pitted against her male counterparts in rock music, but the truth is these men couldn’t have become the stars they were without the influence of Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde described herself as a “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” who dedicated her life to fighting injustice in the world.

Lorde was born in New York City in 1934. When she was young, she would memorize poetry and recite it to express herself. She started writing her own poetry when she could no longer find other people’s poems to represent her thoughts. She graduated from Hunter High School. While she was a student there, her first poem was published in a magazine.

Audre earned a Bachelor’s degree at Hunter College and a degree in library science from Columbia University. She was a librarian in the New York public libraries in the 1960s.

1968 was quite the year for Lorde. Her first volume of poetry was published and she started teaching a poetry course at Tougaloo College in Mississippi. It was here where she was inspired to write her second volume of poetry, Cables to Rage, which talked about themes like racism, sexism, family, love, and her own sexuality.

She had two children with her husband, Edward Rollins, a white gay man, before divorcing him in 1970. In 1972, Audre met her long-time partner, Frances Clayton.

In 1973, Audre’s third volume of poetry was published. It earned much praise and was nominated for a National Book Award. This volume was more political than her other volumes.

Lorde wrote about challenges she faced, including racism, sexism, and homophobia. In one poem called “Power,” she wrote about a black 10-year-old child who was shot by the police. After the officer was acquitted, she wrote the poem about the rage she felt when she’d found out the verdict.

In the 1980s, Audre Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer. She documented her experiences with it in her most famous nonfiction work, The Cancer Journals. Lorde got a mastectomy in hopes of ridding herself of the disease. She rejected the idea that she was a victim, and instead called herself and other women who had gone through the same experience “warriors.”

Eventually, the cancer spread to her liver. In total, Audre battled cancer for over a decade. She spent the last few years of her life in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Lorde died in November 1992 at the age of 58. Over her career, she earned many awards. She is remembered for being a warrior against injustices in the world.

Sources

Marsha P Johnson

https://ucnj.org/mpj/about-marsha-p-johnson/

https://wams.nyhistory.org/growth-and-turmoil/growing-tensions/marsha-p-johnson/

https://gothamist.com/arts-entertainment/marsha-p-johnson-statue-bust-christopher-park

Jackie Mitchell

https://www.mlb.com/news/meet-jackie-mitchell-the-girl-who-struck-out-babe-ruth

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/07/obituaries/jackie-mitchell-overlooked.html

Frances Perkins

https://francesperkinscenter.org/life-new/

Sister Rosetta Tharpe

https://afropunk.com/2019/03/rosetta-tharpe/

Audre Lorde

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/audre-lorde

https://www.biography.com/writer/audre-lorde